What is bladder cancer?

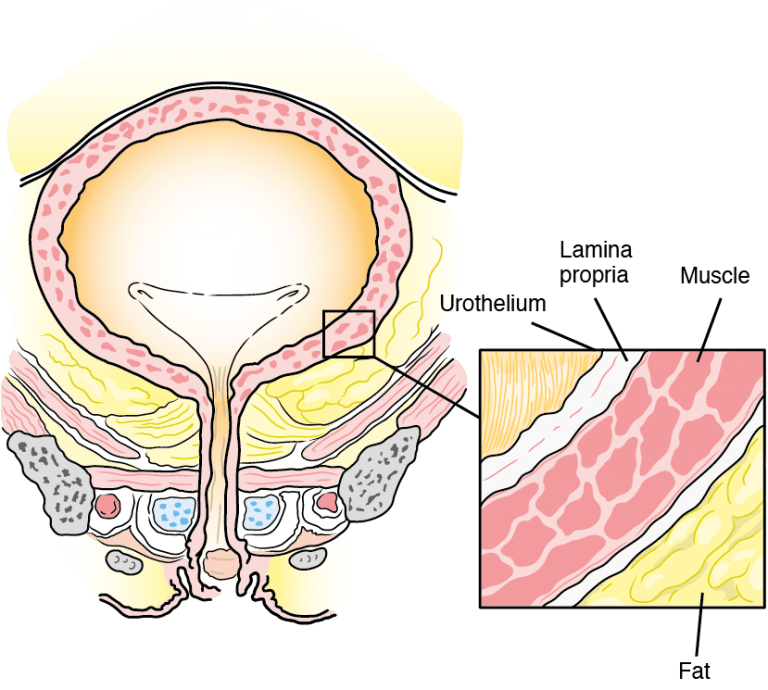

Cancer occurs when cells in the bladder start to grow out of control. Most tumors develop on the inner layer of the bladder. Some can grow into the deeper bladder layers. As cancer grows through these layers into the wall, it becomes harder to treat. The lining, where tumors initiate, is also found in the inner layers of the kidneys, ureters, and urethra. So, similar cancers can occur in these areas, though much less frequently.

What does your bladder do?

Your bladder is part of your urinary system. The job of the urinary system is to filter waste products from your blood and transport the waste products or urine, out of your body. The diagram below shows the organs of the urinary system. Most of the urinary tract is lined with a special layer of cells called transitional cells. The primary “machines” in the human filtering system are the two kidneys located close to the backbone and protected by the ribs. The kidneys work independently. They have the significant task of filtering approximately 20% of total blood volume each minute and removing the by-products of digestion and of other body functions.

Once produced, the urine (the filtered waste product) is stored in the central part of the kidney called the renal pelvis. At regular intervals, the renal pelvis contracts and propels the urine through the ureters. These narrow, thin-walled tubes extend from inside the renal pelvis to the bladder. The bladder is a thick-walled structure, consisting of a relatively thin inner layer with a thick muscle covering.

This inner layer or epithelium is made of several layers of cells. The epithelial layer is also called the transitional cell layer. The main function of the bladder is to store urine. For most people, the bladder can hold as much as 1 pint (16 ounces) of urine at a time. It contracts or expands depending on how much fluid is in it. When it contracts following a series of neurological “messages” to the brain and spinal cord, the urine moves through the urethra outside the body.

Symptoms, Signs, and Risk Factors

What are bladder cancer signs and symptoms?

The most common clinical sign of bladder cancer is painless gross hematuria, blood in the urine that can easily be seen. Two features that tend to mask the severity of the gross hematuria and may influence patients to postpone seeking immediate medical care are 1) the bleeding may be occasional and short-lived; and 2) there is likely to be no pain associated with the bleeding. In addition, it may be that the tumors do not produce enough blood for a patient to see (microscopic hematuria) and are only detected with the help of special chemicals and/or a microscope after a urine test is done by a physician.

However, blood in the urine does not necessarily mean a diagnosis of bladder cancer. Infections, kidney stones as well as aspirin and other blood-thinning medications may cause bleeding. In fact, the overwhelming majority of patients who have microscopic hematuria do not have cancer.

Irritation when urinating, urgency, frequency and a constant need to urinate may be symptoms a bladder cancer patient initially experiences. Oftentimes, though, these are merely symptoms of a urinary tract infection and antibiotics become the first line of treatment. To make the necessary distinction between an infection and something more serious, it is critical that a urinalysis and/or culture are done to detect any bacteria in the urine. If the culture is negative for bacteria, patients should be referred to a urologist for further testing.

What are the bladder cancer risk factors?

- Smoking: Smoking is the greatest risk factor. Smokers get bladder cancer twice as often as people who don’t smoke. Get tips on Smoking Cessation

- Chemical Exposure: Some chemicals used in the making of dye have been linked to bladder cancer. People who work with chemicals called aromatic amines may have higher risk. These chemicals are used in making rubber, leather, printing materials, textiles and paint products.

- Race: Caucasians are twice as likely to develop bladder cancer as are African Americans or Hispanics. Asians have the lowest rate of bladder cancer.

- Age: The risk of bladder cancer increases as you get older.

- Gender: While men get bladder cancer more often than women, recent statistics show an increase in the number of women being diagnosed with the disease. Unfortunately, because the symptoms of bladder cancer are similar to those of other gynecologic and urinary diseases affecting women, women may be diagnosed when their disease is at a more advanced stage.

- Chronic bladder inflammation: Urinary infections, kidney stones and bladder stones don’t cause bladder cancer, but they have been linked to it.

- Personal history of bladder cancer: People who have had bladder cancer have a higher chance of getting another tumor in their urinary system. People whose family members have had bladder cancer may also have a higher risk.

- Birth defects of the bladder: Very rarely, a connection between the belly button and the bladder doesn’t disappear as it should before birth and can become cancerous.

- Arsenic: Arsenic in drinking water has been linked to a higher risk of bladder cancer. Learn more about water pollutants and bladder cancer.

- Earlier Treatment: Some drugs (in particular Cytoxan/cyclophosphamide) or radiation used to treat other cancers can increase the risk of bladder cancer.

- Some drugs (in particular Cytoxan/cyclophosphamide) or radiation used to treat other cancers can increase the risk of bladder cancer.”

Types, Stages, and Grades

What are the types of bladder cancer tumors that may form?

Three types of bladder cancer may form, and each type of tumor can be present in one or more areas of the bladder, and more than one type can be present at the same time:

- Papillary tumors stick out from the bladder lining on a stalk. They tend to grow into the bladder cavity, away from the bladder wall, instead of deeper into the layers of the bladder wall.

- Sessile tumors lie flat against the bladder lining. Sessile tumors are much more likely than papillary tumors to grow deeper into the layers of the bladder wall.

- Carcinoma in situ (CIS) is a cancerous patch of bladder lining, often referred to as a “flat tumor.” The patch may look almost normal or may look red and inflamed. CIS is a type of nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer that is of higher grade and increases the risk of recurrence and progression. At diagnosis, approximately 10% of patients with bladder cancer present with CIS.

While the majority of bladder cancers (approximately 90-95%) arise in the bladder, the urothelial cells that line the bladder are found in other locations in the urinary system. Sometimes these urothelial cancers can occur in the lining of the kidney or in the ureter that connects the kidney to the bladder. This is known as upper tract urothelial cancer (UTUC) correspond to a subset of urothelial cancers that arise in the urothelial cells in the lining of the kidney (called the renal pelvis) or the ureter (the long, thin tube that connects that kidney to the bladder).

What is meant by “staging and grading” a tumor?

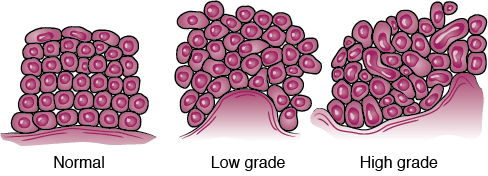

If bladder cancer is diagnosed, the doctor needs to know the stage, or extent, of the disease to plan the best treatment. Staging is a careful attempt to find out whether the cancer has invaded the bladder wall, whether the disease has spread, and if so, to what parts of the body. Grade refers to what the cancer cells look like, and how many cells are multiplying. The higher the grade, the more uneven the cells are and the more cells are multiplying. Knowing the grade can help your doctor predict how fast the cancer will grow and spread.

Urologists typically send a sample of the cancer tissue to a pathologist, a doctor who specializes in examining tissue to determine the stage and grade of the cancer. The pathologist writes a report with a diagnosis, and then sends it to your urologist.

What are the different “stages” for a bladder cancer tumor?

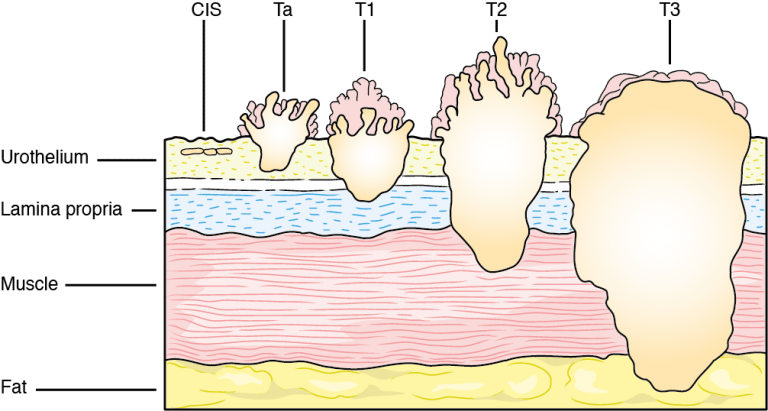

Stage suggests the location of the tumor in relation to the inner lining of the bladder. The higher the stage the further the tumor has grown away from its original site on the surface. The following are the stages for bladder tumors:

T0: No tumor

Ta: Papillary tumor without invading the bladder wall

TIS (CIS): Carcinoma in situ (non-invasive flat high-grade (G3) cancer)

T1: Tumor invades the connective tissue under the surface lining

T2: Tumor invades the muscle layer

T3: Tumor penetrates the bladder wall and invades the surrounding fat layer

T4: Tumor invades other organs (i.e., prostate, uterus, vagina, pelvic wall)

What are the different “grades” for a bladder cancer tumor?

Grade is expressed as a number between 1 (low) and 3 (high, i.e. G3); the higher the number the less the tumor resembles a normal cell. In lieu of numbers to grade a bladder cancer tumor, your doctor may refer to the tumor simply as low or high grade.

Treatment

What types of bladder cancer treatments are available?

Knowing the stage and grade of your tumor helps your doctor decide which methods are most suitable for treating your cancer. It is important to remember that bladder cancer patients must expect to be closely followed by their urologists, with regularly scheduled cystoscopies and urine cytology as bladder tumors often recur. Early detection is crucial to a good long-term prognosis.

Ta papillary tumors are usually low grade (most closely resemble normal cells) and, even though a large majority will recur multiple times after the initial diagnosis and removal, 85-90% will never invade the bladder wall and become life-threatening. Further treatment beyond removal may not be necessary, but regular follow-up is required.

Although CIS is also non-invasive, as the tumor has not grown into the lamina propria (the layer of blood vessels and cells that is situated between the bladder lining and the muscle wall), it is more aggressive than Ta non-invasive tumors and will probably be treated with more aggressive therapies, including intravesical immunotherapy (BCG). Once the tumor has invaded the lamina propria, it is considered an invasive tumor with the potential of spreading through the muscle wall and ultimately affecting organs that border the bladder (prostate, uterus, etc.) or other organs such as the lung, bone, and liver. Intravesical therapy and surgery may be considered. If invasion of the muscle is seen on the biopsy, the tumor is at least stage T2, in which case more aggressive treatments (surgery, radiation, and/or chemotherapy) are typical considerations.

There are many lymph nodes that also surround the bladder. Lymph nodes are small glands that store the white blood cells that help to fight disease throughout the body. Cancer cells from invasive bladder tumors may appear in the lymph nodes. Although they can often only be seen with a microscope, they may be seen on scans as enlarged lymph nodes – cancer cells in the lymph nodes indicate that the tumor has spread and will influence the management of the bladder cancer patient. Chemotherapy may be suggested.

Transurethral Resection of a Bladder Tumor (TURBT)

Generally, after the diagnosis of a bladder tumor, the urologist will suggest that the patient have an outpatient procedure in the hospital to examine the bladder more completely under anesthesia (general or spinal) and to remove, if possible, those tumors which are suitable for resection. The doctor may refer to this procedure as a TURBT (transurethral resection of a bladder tumor).

The bladder cancer TURBT is “incision-less” surgery usually performed as an outpatient procedure. It is the first-line surgical treatment for bladder tumors. Like the cystoscope, the resectoscope, the instrument used to remove the tumor in the TURBT, is introduced through the urethra into the bladder. Attached to this scope is a small, electrified loop of wire which is moved back and forth through the tumor to cut and remove the tissue. Newer technology known as “blue light” cystoscopy uses an optical imaging agent is often used during this procedure at major medical centers.

Electricity is also used to seal off bleeding vessels. This is sometimes called electrocauterization or fulguration. One of the advantages of this procedure is that it can be performed repeatedly with minimal risk to the patient and with excellent results. There is less than a 10% risk of infection or injury to the bladder, and both are easily correctable.

The most common risks of the TURBT are bleeding, pain, and burning when urinating and all three are temporary. If the bladder tumor is large, the urologist may choose to leave a catheter in the patient’s bladder for a day or two to minimize problems occurring from bleeding, clot formation in the bladder or expansion of the bladder due to possible storage of excess urine or blood. Even if the tumor is small, a catheter may be inserted to rinse the bladder out if the bleeding persists.

All the specimens from the TURBT will be sent to the pathologist for review. The pathologist will confirm the type of bladder cancer and the depth of invasion into the bladder wall, if any. These findings, along with results from imaging such as CT scans, will determine if further treatment is necessary.

Click here to read our Get the Facts | TURBT (PDF), filled with advice from patients who have experienced it.

Intravesical Therapy

Certain types of bladder tumors are hard to remove using surgical procedures like a TURBT, particularly flat tumors (carcinoma in situ). In addition, some tumors may be likely to recur after initial resection. In these cases, special medications that destroy cancer cells may be placed directly into the bladder. This treatment is called intravesical therapy.

There are two principal drugs that are used as intravesical chemotherapy or immunotherapy:

Bacille Calmette-Guerin or BCG

An intravesical immunotherapy that causes an immune or allergic reaction that has been shown to kill cancer cells on the lining of the bladder. BCG is often preferred for patients who have high-grade tumors or who have CIS or T1 disease.The urologist may also suggest maintenance therapy using BCG. The rationale for maintenance therapy is that the initial therapy plus intermittent therapy for 2 to 3 years may provide a decreased likelihood that the tumors will recur. The disadvantage to maintenance therapy is prolonged bladder irritation, fever, and bleeding which may force the doctor to decrease the BCG dosage or to discontinue the therapy. Both Mitomycin C and BCG are administered through a catheter which is placed in the bladder through the urethra. The drug is then introduced into the bladder.

Mitomycin C

An intravesical, anti-cancer drug that has been shown to be effective after the TURBT in reducing the number of recurrences of bladder tumors by as much as 50%. An advantage of Mitomycin C is that it is not easily absorbed through the lining of the bladder and into the blood and, thus, less risky than chemotherapy given intravenously. Side effects from the drug can be pain when urinating and/or “chemical cystitis”, an irritation of the lining of the bladder which can feel like a urinary tract infection. Both these side effects are temporary and will disappear when the therapy is stopped. This drug may be delivered into the bladder immediately after TURBT. For more information, see the video above about TURBT and intravesical chemotherapy.

For some patients, Valrubicin may be used. The drug is indicated for patients whose CIS bladder cancer did not respond to BCG treatment or and who cannot have surgery right away to take out the bladder.

Click here to read our Get the Facts | BCG (PDF), filled with advice from patients who have experienced it.

Bladder Removal Surgery

If a bladder tumor invades the muscle wall or if CIS or a T1 tumor still persists after BCG therapy, the urologist may suggest removal of the bladder or a radical cystectomy. Before any radical surgery is performed, a series of CT scans or an MRI will be ordered to exclude the possibility of metastatic or “distant” disease in other parts of the body. If the patient has metastatic disease, surgery to remove the bladder is not recommended and patients will be referred to a medical oncologist to discuss chemotherapy. The two types of surgery performed for muscle-invasive bladder cancer are partial or complete radical cystectomy.

Partial cystectomy is fairly uncommon and is only performed:

- if the muscle-invasive bladder tumor is the first and only bladder tumor the patient has had and

- if the tumor is in a location where it is easily accessible for surgery and, if removed, will leave the bladder with enough capacity for the patient to have normal bladder function.

A complete radical cystectomy requires complete bladder removal, and in men, almost always involves removal of the prostate as well. For women, in addition to removing the bladder, the surgeon may also remove the uterus, fallopian tubes, ovaries and cervix, and occasionally a portion of the vaginal wall. In addition, the surgeon will remove lymph nodes surrounding the bladder, and perhaps even more, to determine whether the cancer has progressed to the lymph nodes, which then could result in metastasis. The lymph node removal is an important method of accurately staging the progression of the disease. Cystectomy can be performed through an open incision or laparoscopically, typically with robotic assistance. Removal of the bladder also requires the surgeon to create a passage for the urine to go from the kidney to outside the body. Even though the bladder is removed, the kidneys, ureters and urethra are still in place. Because no artificial bladder has yet been invented that is tolerated by the urinary tract system, the urologist has learned to create the passageway or conduit between the kidneys and ureters and the urethra using a piece of the patient’s own intestine.

Click here to read our Get the Facts | Radical Cystectomy (PDF), filled with advice from patients who have experienced it.

Chemotherapy

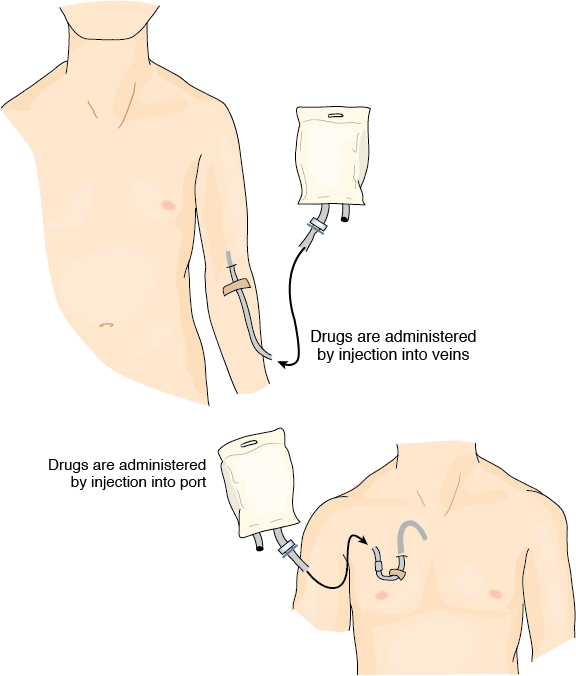

Chemotherapy refers to drugs used to treat cancer systemically. These drugs are administered by injection directly into the patient’s veins, and circulate through the bloodstream to attack cancer cells anywhere in the body. Chemotherapy is typically used to treat bladder cancer that has metastasized, which means the cancer cells have spread beyond the bladder to other organs.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is the term used for chemotherapy prior to surgery. An important clinical trial has shown that the use of intravenous chemotherapy before radical cystectomy improves survival for patients with invasive bladder cancer. This type of initial chemotherapy, termed neoadjuvant chemotherapy, works to shrink the tumor within the bladder and may also kill small metastatic deposits of disease that have spread beyond the bladder. It is important to note that it does not appear that single-agent chemotherapy is helpful in improving the survival of patients with locally advanced bladder cancer. The two regimens recommended for neoadjuvant treatment are either Dose Dense MVAC or GC (discussed below).

Adjuvant chemotherapy is the term used for chemotherapy following surgery. Typically, removal of the bladder also involves removal of a number of lymph nodes surrounding the bladder, which are then sent to the pathology lab for analysis. If the pathology results indicate that the cancer has spread to the lymph nodes, the doctor may recommend chemotherapy to help prevent any cancer recurrence. Dose Dense MVAC or GC are typically recommended in this setting.

If bladder cancer is found to have spread to other sites, systemic chemotherapy is recommended. It is very difficult to permanently cure metastatic bladder cancer. In most cases, the goal of treatment is to slow the spread of cancer, achieving shrinkage of tumor, relieving symptoms, and extending life as long as possible.

What type of chemotherapy is used for bladder cancer?

Cisplatin based chemotherapy has been the standard treatment for bladder cancer for many years, based on the results of clinical trials from the 1990s. The two regimens most commonly used are dose-dense (DD) MVAC and GC. MVAC uses four drugs: methotrexate (MTX, Amethopterin, Rheumatrex, Trexall), vinblastine (Velban), doxorubicin (Adriamycin, Rubex), and cisplatin (Platinol). The advent of effective anti-nausea medication and injections that can keep immune systems from being depleted by chemotherapy have improved our ability to give MVAC safely on an accelerated dose dense schedule. The NCCN now recommends MVAC be given according to the “dose dense or DD” schedule due to improved toxicity and suggested improvement in efficacy compared with the standard schedule. A clinical trial conducted in the late 1990s showed that the combination of gemcitabine (Gemzar), plus cisplatin (GC), gives similar anticancer effects to standard MVAC combination. Both GC and DD MVAC have been useful in bladder cancer in delaying recurrence, extending life and sometimes achieving cure, and both regimens are routinely used in the neoadjuvant and metastatic settings. Clinical trials are underway to assess whether the addition of another agent to these regimens improves outcomes.

Is combination chemotherapy and radiation used for bladder cancer treatment?

In recent years, chemotherapy and radiation have been combined to provide a “bladder preservation” therapy for higher risk (i.e. muscle-invasive) cases. In the past radiation therapy alone was used because it effectively shrunk tumors. Bladder cancers are chemosensitive and therefore adding combined chemotherapy (multiple chemotherapeutic agents given together) to radiation has improved results. To ensure the success of bladder preservation therapy, there are at least three requirements which should be met: 1) a “complete” resection of the tumor(s) by TURBT; 2) no obstruction of 1 or both kidneys as a result of the bladder tumor; and 3) no T4 bladder tumors.

If the tumors do not respond to an initial course of chemotherapy and radiation, it may be reasonable to perform, if medically possible, a cystectomy.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy is a type of cancer treatment that helps a person’s immune system recognize and attack cancer cells.

The immune system detects and protects the body from anything it perceives as foreign, such as viruses, bacteria and even cells that are abnormal because they are cancerous. However, cancer has found ways to evade the immune system. Cancer immunotherapy is designed to help the immune system recognize cancer cells and activate specific immune cells to target and attack them. As a potential side effect, immunotherapy could cause the immune system to attack normal organs and tissue in the body. The two most common types of immunotherapy are BCG and checkpoint inhibitors. Checkpoint inhibitors are typically specific to certain gene mutations.

There are now a number of new immunotherapies approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for certain people with a type of bladder cancer called locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. Your doctor can help you determine if you might be a candidate for this treatment option.

Click here to read our Get the Facts | Immunotherapy (PDF) that covers what to expect before, during, and after this treatment.

Bladder Preservation With CMT

What is combined-modality therapy?

For all the sites in the body where cancer may arise, modern therapies are increasingly looking towards eradicating the cancer while at the same time preserving the affected organ (bladder, breast, voice box) and giving the patient the best possible functional outcome and thus quality of life. This is usually achieved by the combination of lesser surgery, with radiation, and chemotherapy, all in lower doses than if used alone. Modern Combined-Modality Therapy (CMT) for bladder cancer follows just that pattern. It begins with an aggressive resection of the visible tumor then following it with Radiation Therapy (RT) given together with chemotherapy. The latter makes the remaining tumor more sensitive to the radiation. When patients are well selected for this approach it can offer equal cure rates to treating with a cystectomy while still preserving a functioning bladder. This approach is favored for patients who are strongly motivated to maintain their bladder or in patients who have so many other medical problems that a radical cystectomy is simply not a safe option.

Who is suitable for bladder preserving therapy by CMT and how are they to be followed?

Many factors play into the determining which patients with Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer (MIBC) are suitable for CMT. Ideally, these patients would have cancers with the usual urothelial histology (a small proportion have different appearance down the microscope). They would have clinical stage T2 to T3a disease, and the absence of hydronephrosis (the partial obstruction by the tumor of the ureter that transmits the urine from the kidney to the bladder). In addition, the best candidates are those with tumors small enough to have been visibly completely resected at TURBT. If a visibly complete resection is performed then the radiation and chemotherapy have only to mop up the remaining microscopic cells, a much easier prospect.

Following treatment patients must be followed closely with cystoscopy surveillance to detect any cancer recurrence or development of a new primary tumor in the bladder or elsewhere within the urogenital tract (ureters, bladder, urethra).

A minority of patients will have cancers that do not respond completely or who develop an invasive recurrence after CMT. For them, a “salvage” cystectomy is recommended and a significant number can be cured in this fashion.

The subsequent quality of life of patients after treatment

The primary objective of CMT is to cure while preserving the bladder. Bladder preservation only has merit, however, if the preserved bladder and other pelvic organs function at acceptable levels after treatment. Patients should expect some degree of temporary urinary irritative symptoms and bowel symptoms during treatment but this is to be distinguished from serious irreversible complications that the physicians now strive to avoid. The patient’s baseline urinary function before treatment is an important consideration, since patients with very poor baseline urinary function may not have a “bladder worth sparing.”

Consensus Guidelines

Multiple national and international medical agencies have now developed consensus guidelines and all recommend the use of combined-modality therapy (CMT) for many presentations of muscle-invasive bladder cancer. The approaches presented here are consistent with these guidelines. In addition, several patient advocacy groups serve as good resources for providers and patients. For example, the Bladder Cancer Advocacy Network is the largest community of bladder cancer survivors, and medical and research professionals and advocates that offers education and support to patients and providers and funding to advance research for bladder cancer.

Click here to read Bladder Preservation with Combined-Modality Therapy (CMT) | An Expert Explanation (PDF) for the full and more in-depth informatio

Palliative Care

Palliative care is specialized medical care for people with serious illness. This type of care focuses on providing relief from the symptoms and stress of a serious illness. Palliative care also treats emotional, social, practical, and spiritual problems that illnesses can bring up. The goal is to improve the quality of life for both the patient and the family.

Who gives Palliative Care?

Palliative care is an interdisciplinary team approach. Any health care provider may provide palliative care by addressing the side effects and emotional aspects of cancer. There are health care providers, like physicians and nurses, who are specially trained in palliative care and work with, not in place of, your primary oncology team. A palliative care team may also include social workers, pharmacists, registered dietitians, chaplains, NPs, physician assistants, and therapists.

When is Palliative Care used in cancer care?

Palliative care is incorporated to promote the best quality of life (QOL) throughout a patient’s cancer experience. Palliative care can be given at the same time as treatments meant to cure or treat the disease. A patient can receive palliative care when bladder cancer is diagnosed, throughout treatment, during follow-up, and at the end of life.

Where is Palliative Care received?

Palliative care is offered at many cancer centers, clinics, inpatient units at hospitals, and at home.

What are some issues faced by bladder cancer patients that can be addressed in palliative care?

All patients are unique and have specific needs. The following list provides examples and is not exhaustive:

Physical

- Pain or other complications from the cancer itself, treatments or surgery

- Nausea/vomiting during and after chemotherapy or other treatments

- Fatigue during BCG treatments, radiation, or during chemotherapy or

- Sexual problems caused by surgery or other treatments

- Nutritional status before, during and after cancer therapies or surgery

Emotional

- Supportive care for feelings of depression, anxiety, or fear for patients and their families

- Sadness about body changes with post-surgery urinary diversion management

- Talking to children and other loved ones about cancer

Spiritual

- Incorporate spiritual care according to patient/family needs, values, beliefs and culture background

Other

- Questions about legal forms such as advanced directives and health care power of attorney

Is Palliative Care the same as hospice?

No. This is a common misconception about palliative care. Palliative care is offered much earlier in the disease process. While all of hospice is palliative care, not all of palliative care is hospice. Patients can be transitioned to hospice once cancer treatments are no longer controlling their disease, therefore receiving palliative care only. While patients are still receiving cancer treatment, they may receive palliative care in addition to their cancer treatments.

Myths about Palliative Care

1. If I get palliative care, that means I can’t have any more cancer treatment: FALSE.

Incorporating palliative care into your cancer care has resulted in higher patient satisfaction. If your cancer doctor refers you to a palliative care specialist, they will work together to optimize your quality of life.

2. I don’t have pain, so I can’t get palliative care: FALSE.

Palliative care addresses much more than just pain. Examples of issues that are addressed in palliative care include nausea, vomiting, fatigue, appetite loss, sleeping problems, depression, anxiety, and much more.

3. I didn’t get chemotherapy for my bladder cancer, so I can’t get palliative care: FALSE.

Some patients experience bad bladder symptoms after treatments like BCG or radiation, and pain or bowel problems after surgery. Palliative care can be used for these types of problems, too.

Click here to read our Get the Facts | Palliative Care (PDF) that covers what to expect before, during, and after this treatment.